Ulster and Delaware Railroad

| Ulster and Delaware Railroad | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reporting marks | UD |

| Locale | Kingston Point, NY to Oneonta, NY, Hunter, NY & Kaaterskill, NY |

| Dates of operation | 1875 – passenger service: 1954 - freight service: 1976 |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8½ in (1435 mm) (standard gauge) |

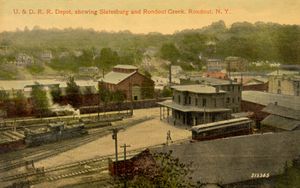

| Headquarters | Rondout, NY |

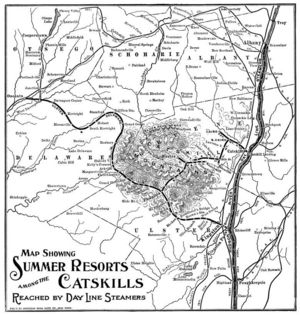

The Ulster and Delaware Railroad Company (U&D) was a small Class III railroad located in New York State, headquartered in Rondout and founded in 1866. It was often advertised as "The Only All-Rail Route To the Catskill Mountains." At its greatest extent, the U&D ran from Kingston Point, on the Hudson River through the heart of the Catskill Mountains to its western terminus at Oneonta, passing through four counties (Ulster, Delaware, Schoharie and Otsego), with branches to Kaaterskill and Hunter in Greene County. The U&D connected with five other railroads: the West Shore, Wallkill, and O&W in Kingston, the D&N in Arkville, the Cooperstown & Charlotte Valley in West Davenport, and the D&H in Oneonta.

Although a small railroad, it was big in stature, as it went through many favored tourist hot-spots. Many elegant hotels kept business going, some of which were sponsored or built by the railroad. Besides the passenger business, there were also plenty of farms and creameries (most of them in Delaware County) as well as businesses shipping coal, stone, ice and various wood products.

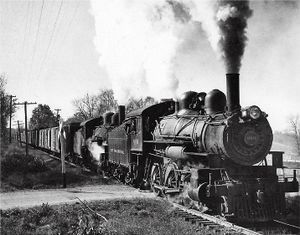

One of the few downfalls were the many grades, some as steep as 4.4%. A train took almost four hours to get from Kingston Point to Oneonta, running at an average speed of only 30-40 MPH, although some sections permitted running at 60 MPH or more. When roads improved and automobiles became more widely available, the advantages of train travel were nil.

Contents

- 1 History

- 2 Present condition

- 3 References

- 4 See also

- 5 External links

History

Rondout and Oswego Railroad

In the early 1800s waterways formed the principal transportation network in New York. An important point on this network was Rondout. Located at the confluence of the Rondout Creek and the Hudson River, in 1828 it became the eastern terminus of the Delaware and Hudson Canal. Here cargo and passengers were transferred from canal boats to the larger vessels navigating the Hudson.

By the end of the Civil War, it was clear that railroads were pre-empting waterways as the preferred method of transportation. Thomas C. Cornell, founder of the Cornell Steamboat Company and a resident of Rondout was among those who took notice. Although Cornell made plenty of money from shipping, he envisioned a railroad that would bring supplies from ports in central or western New York to his port in Rondout. So Cornell chartered the Rondout and Oswego in 1866, with himself as the first president.

Cornell decided to construct this new railroad of 62- and 70-pound rail. It would go from Rondout to the busy city of Oneonta, and then on to Oswego on the shore of Lake Ontario. The R&O reached the summer vacation hot-spot of Olive Branch in 1869, with the railroad now being about 12 miles long. By the next year, in 1870, the first train was run, and the railroad was finally in an operational state. It was extended to Phoenicia in 1870, and there the railroad built a stucco station across the Esopus Creek from the village. [1] The same year, ownership of the railroad was handed over to John C. Brodhead [2] and later that year was the small town of Big Indian. By 1871 construction reached Dean's Corner's (now Arkville) (where it would eventually join the Delaware and Northern). However, the R&O folded upon completing construction to Roxbury, and the task of constructing the remainder of the route was left to its newly organized successor, the New York, Kingston & Syracuse (NYK&S).

It was a very successful railroad with plenty of passengers coming up from surrounding towns and bigger cities. Steamboat passengers could dock at Rondout and transfer to the railroad. Later, passengers could also transfer at Kingston, first via the Wallkill Valley Railroad (1872), then via the West Shore Railroad (1881), and much later via the New York, Ontario and Western (1902). From the boats it was a short walk to the R&O station to transfer to the train. Freight was also very well handled. A lot of the freight income was made off coal shipped along the D&H Canal from the Moosic Mountains near Carbondale, Pennsylvania to the port at Rondout. There were also plenty of vegetables, fruit, and milk from the farms in the Catskills and the other parts of New York.

While steadily grading to Moresville (present-day Grand Gorge), the high number of curves andgrades created a big problem, as more digging, ties, and rails meant higher costs to complete the rest of the railroad. The railroad couldn't make enough money to pay off the debt and continue building the railroad, so in 1872, R&O ownership was temporarily transferred to John A. Greene for a period of 10 years. Greene was expected to have the railroad finished to the town of Oneonta by 1874, pay all of the debts, and withstand future debts of up to $700,000. However the railroad was slowly losing money and eventually had to cut service before going bankrupt in 1872. Later that year it was re-organized as the New York, Kingston and Syracuse Railroad to continue with the project. [1]

New York, Kingston and Syracuse Railroad

After the Rondout and Oswego went bankrupt in 1872, it was quickly re-organized as the New York, Kingston and Syracuse Railroad (NYK&S), under the leadership of George Sharpe. The plan of going to Oswego was now gone, and the new plan was to go to Oneonta and make a sharp turn north to Earlville, New York, where it would make a connection with the recently constructed Syracuse and Chenango Valley Railroad. Construction of the railroad had immediately begun, and the railroad was extending very fast. Within the year of 1872, it had already reached the townships of Roxbury, Gilboa and Stamford, with the first train arriving in the village of Stamford late that year.

This increased service provided the first real rail route into the Catskills benefiting both passenger and freight customers. The railroad was further benefited by the many connections to other railroads enabling passengers as far away as New York City to visit the Catskills (via the newly constructed Wallkill Valley Railroad and its connection to the Erie Railroad). Another boon to business was a ferry that ran across the Hudson to Rondout from Rhinebeck where a Rhinebeck and Connecticut Railroad station (the current Amtrak station), connecting the cities of Hartford, Connecticut, Providence, Rhode Island and Boston, Massachusetts to the region.

The town (and later city) of Kingston, New York was extremely profitable to the railroad due to the large number of industries including cement, concrete, bricks, and bluestone. Additionally, Kingston was also a popular passenger stop, as people would rely on the railroad to take them around the Catskills to jobs at mills and small factories.

Although this prosperity seemed good on the surface, there was bad news, as well. The NYK&S still wasn’t profitable enough to steer clear of bankruptcy. So in 1873, the NYK&S designated the Farmers Loan and Trust Company as trustee for the first mortgage bondholders of the railroad. While this helped for a short time, it was only another two years until even the trustee finally couldn't handle the railroad’s problems. So the railroad eventually went bankrupt in 1875 and was sold under foreclosure to the bank. It was re-organized as the Ulster and Delaware Railroad later that year. [1]

Ulster and Delaware Railroad

Stony Clove and Catskill Mountain Railroad

Cornell got the idea for another railroad that would start at the current in Phoenicia and go up along the Stony Clove Valley to the bustling village of Hunter, New York. He decided to call it the Stony Clove and Catskill Mountain Railroad. Unlike the U & D it would utilize a three-foot gauge which ostensibly would be cheaper to build and operate. Construction started on the railroad in 1881, with Cornell's son-in-law, Samuel Decker Coykendall supervising the construction. Originally planned as a summer-only operation serving the Ulster County communities of Phoenicia and Chichester, and the Greene County villages of Lanesville, Edgewood, and Hunter, the service was expanded to year-round operation. In addition to the major stations, there was a flagstop at the Stony Clove Notch and also a station between the Notch and Hunter called Kaaterskill Junction Station (originally Tannersville Junction Station) at the junction of the Kaaterskill Railway.

The difference in gauge between the U&D and SC&CM caused difficulties in transfering rolling stock from the mainline. So in 1882, the two companies installed a Ramsey Car Transfer Apparatus in the yard at Phoenicia. This device allowed the standard-gauge equipment to be run on the narrow-gauge line. With the apparatus, the transfer only took about eight minutes saving the railroads lots of time and money.

Industries on this line included the William O. Schwartzwalder Furniture Factory in the company-owned town of Chichester. Other big companies included the Fenwick Lumber Company in Edgewood andthe Horatio Lockwood & Company Furniture Factory in Hunter. The railroad was taken over by the U&D in 1892, and these industries now had a new railroad to transport their products. [3]

Kaaterskill Railroad

This was another three-foot gauge railroad that went from the SC&CM's Kaaterskill Junction Station, crossed the immense Light Dam Bridge (named after the electric company using the dam), and went to the bustling town of Tannersville, where over half of the freight on the Kaaterskill Railroad was handled. After this, it crossed a six-span bridge, the biggest on the line, before reaching Haines Falls. There, it reached a pathway up to the elegant Laurel House, where there was another station, and a view of Kaaterskill Falls. Finally it reached Kaaterskill where the competing Catskill & Tannersville paralleled the line. The C&T also served as a 0.93-mile extension to the Otis Summit Station. This station was at the western end of the Otis Elevating Railway, which went up the Catskill Escarpment to the famous Catskill Mountain House.

The KRR was taken over by the U&D in 1892. A year later, in 1893, the Catskill and Tannersville Railway, obtained trackage rights to the KRR. It also leased the entire line, including the rest of its own right-of-way (ROW) to the Catskill Mountain House. The C&T used the KRR's locomotives and equipment allowing passengers a direct ride to the Mountain House. [3]

Ulster and Delaware Railroad

The Ulster and Delaware wasn't at the peak of Cornell's interests. He had completed the Rhinebeck and Connecticut Railroad in 1870, along with chartering the Kaaterskill Railroad in 1884. He was also the president of the Wallkill Valley Railroad. Because he was preoccupied with these other railroads, he ordered other railroads to be chartered to go to Oneonta. His first attempt was the Hobart Branch Railroad, which would start at Stamford, and then go to Oneonta. However, it only made it to Hobart in 1884 before it was incorporated into the U&D later that year. His next attempt was the Delaware and Otsego Railroad which was also incorporated into the U&D by 1887. Since neither of these attempts worked, Cornell refocused his attention on the Ulster and Delaware. He continued with its construction until his death in 1890.

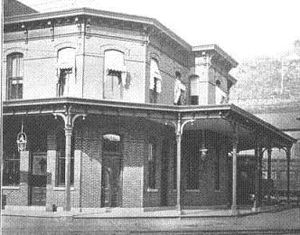

The next year in 1891, Edwin Young took the presidency. He kept the railroad from being sold to a bigger railroad until he died in 1893. After Young, the railroad would go through presidents Horace Greeley Young and Robert C. Pruyn, each having a one-year term, until it got a new president in 1895,[2] Cornell's stepson, Samuel Decker Coykendall. In 1895, the eastern terminus was extended from Rondout to Kingston Point where steamboats could dock and directly transfer passengers, another town eventually incorporated into Kingston. However, it took five more years before the railroad finally got to Oneonta in 1900. [1]

The U&D took over the Stony Clove and Catskill Mountain Railroad and the Kaaterskill Railroad in 1892, and ran them as the Narrow Gauge Division. However, between 1898 and 1899, the Narrow Gauge Division was converted to standard gauge and fully incorporated into the U&D in 1903. After the Stony Clove and Catskill Mountain Railroad and the Kaaterskill Railway became part of the Ulster & Delaware, they quickly became the busiest parts of the line. The Stony Clove and Kaaterskill Branch was the combination of the portion of the SC&CM up to Kaaterskill Junction Station, and the Kaaterskill Railroad. This branch was 19 miles (30.5 km) long, and had ten stations. The Hunter Branch, the shortest branch on the line at only 2.66 miles (4.3 km), was the part of the SC&CM that went from Kaaterskill Junction Station to Hunter. It only had two stations but was quite steep with the entire branch being a 4.4% incline. [3]

In 1908, the City of New York purchased 12-miles of the Esopus Valley, a valley that had been gouged out by the Esopus Creek. The area of land that New York City purchased only stretched from Boiceville, New York to West Hurley, New York. This would be used to create the Ashokan Reservoir, a reservoir that would be used to supply New York City with drinking water. However, the mainline of the U&D ran right through the middle of the valley with six stations. Ironically the U&D carried supplies from different points to Brown's Station, which would be used to help make the Olivebridge Dam at Olivebridge. When the project was finished, and the reservoir was about to be flooded, the railroad received $1,500,000, and relocated 12.45 miles (20 km) of track, and replaced the previously-existing 64- and 70-pound (35- and 38.5.-kg) rails with 90-pound (49.5 kg) rails from Kingston to Grand Gorge. [1]

A year after the Olivebridge Dam was completed in 1912, railroad president Samuel Coykendall died, and the railroad was handed down to Samuel's son, Thomas C. Coykendall. The new president, however, retired from office the same year, and ownership of the railroad was given to one of his relatives; Edward Coykendall, who would eventually sell the railroad to the New York Central. [2] The stations at Kelly's Corners and West Davenport were abandoned by the railroad in 1923, as they never generated much business, and the Kingston Point Station was abandoned in 1924 when the steamships stopped toting passengers up and down the Hudson River. Cars and trucks starting growing in popularity over the next decade sapping the railroad of more revenue. Finally the Great Depression struck in 1929 and many people didn't have enough money to buy a train ticket or to pay to keep their products in one of the freight houses. As a result the railroad lost a considerable amount of money finally going bankrupt in 1932. [1]

New York Central Railroad - West Shore Division

Steam era

The NYC wanted to incorporate three mid-western railroads into its system; the Michigan Central, the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railway, and the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern. They were already leased by the NYC, but not fully absorbed into the system because the Interstate Commerce Commission prohibited it. Eventually the ICC hinted that if the NYC bought and ran the U&D, they might let them buy the other railroads. The NYC scoffed at the idea, as the U&D wasn't important enough for them but they wanted to buy the other railroads, so they finally purchased the U&D in late 1931 for a price of $2,500,000, and incorporated it into the NYC in 1932.

They renamed the U&D the [West Shore Catskill Mountain Branch], the Stony Clove and Kaaterskill Branch was shortened to the Kaaterskill Branch, and the Hunter Branch kept its name. The roundhouse at Rondout was destroyed, with a sewer plant taking its place; the station however, was still in use. They also slowed down trains to 35 MPH on the main line, and to 25 MPH on the branches. The stations at Chichester, Lanesville and Edgewood were shut down, the Stony Clove Notch flagstop was entirely destroyed and the siding taken out, and the stations at Kaaterskill Junction, Haines Falls, Kaaterskill, and the Laurel House became summer-only stations. While the main line still had year-round stations, only the stations of Tannersville and Hunter on the branches were. This excluded the West Davenport Station, which had already been closed down in 1923, and eventually burnt down ten years later in 1933. The station at Kelly's Corners was also abandoned in the 1920s, and was eventually demolished upon the widening of State Route 30 in the early 1960's. [3] [4]

As for locomotives, Ulster and Delaware #2, 8, 12-14, 16-19, 20, 24 and 29 were deemed worthless, and were scrapped by the New York Central during the takeover in 1932. The other U&D locomotives had been either scrapped or sold off in the earlier years. However, they kept locomotives #19, 21-23, 25-28, and 30-41 and renumbered them #800-818 in 1936, as the turntables in front of the stations were too small for the regular NYC locomotives, and they were the only ones with mountain-gear brakes that were specially designed for the steep grades in the Catskill Mountains. These locomotives were assigned as "class F-x" and "class F-x light". Locomotive #31, however, was deemed unreliable by the Central, and they sent it to West Albany in 1933 to be scrapped, becoming the first of the heavier CMB locomotives to go. They also introduced two new locomotives to the branch; NYC moguls #1013 and 1076. They were the only engines run on the CMB and the smaller branches until diesels took over.

The NYC's F-x light" class locomotives (#800-807, ex-U&D #19, 21-23 & 25-28), were assigned to work on the Wallkill Valley Branch of the New York Central, which used to be the Wallkill Valley Railroad, as well as working on the CMB. These trains were light, yet powerful, which was what they needed; the high and frail Rosendale Bridge in Rosendale, New York had always been plagued with weight restrictions as the material used to build it in the 1870s and then rebuilt in 1895 was not strong enough to hold a modern locomotive. The locomotives the NYC had been using on the WVB were "Class C" 4-4-0s, and were not as powerful as the U&D's 4-6-0s. They tried using the fx-light locomotives on the Wallkill Valley Branch with great success. Two fx-lights could easily haul a 40-car train on the branch safely across the bridge. They were a lifesaver, and were extensively used until the Central tried out light diesel locomotives on it, and replaced the F-x light locomotives as the main source of power on the WVB. [1]

Between the complaints from passengers of the seemingly endless trip from Phoenicia to Kaaterskill or Hunter, (as the speed limit on the branches was 25 MPH), and the cost of the operation, the railroad applied for and got permission from the ICC to abandon the Kaaterskill and Hunter branches in 1939. The New York Central finally scrapped the branches in 1940. The branches were but a memory, the bridges were gone and the stations now nothing but abandoned rubbish. Only two of them survive to this day; the Hunter Station, now a house, and the Haines Falls Station, a museum at present. [3]

Diesel era

The steam locomotives were used heavily on the CMB and the WVB since 1932, and were used for 17 years after that. However, the Central tried diesel locomotives on the Wallkill Valley and the Catskill Mountain Branches in 1948 and found that they performed better due to not having to make water stops. NYC #809 was scrapped in 1945, locomotives #800 & 807 were scrapped in 1946, locomotives #802, 804 & 811 were sent to West Albany in 1948, leaving only locomotives #801, 803, 805-806, 808, 810 & 812-818, which were then renamed NYC #1218, 1220-1223 & 1225-1231, with #801 keeping its number. The engines that had been scrapped in 1948 were supposed to be renamed as NYC #1217, 1219 & 1224, but weren't reassigned before being scrapped. The last steam engine to run over the CMB was NYC #1226 (ex-NYC #813, and ex-U&D #36). Soon after, all of the remaining U&D steam locomotives were sent to Ashtabula, Ohio to be scrapped in 1949. [4] After that, these branches were diesel only branches, not seeing another steam engine until the a three-mile tourist line from Oneonta to a bridge near West Davenport opened in the 1960s.

The line was entirely dieselized by 1949, and passenger service soon ended in 1954 relegating the CMB to freight service only before slowly abandoning the line completely[1] The Arkville station was nearly destroyed by a runaway milk truck in the 1960s, and the NYC tore the remains of the station down. The Kingston Union Station was abandoned after the end of passenger service. [4] The NYC then got permission from the ICC to abandon the portion from Bloomville to Oneonta in 1965, and scrapped the abandoned portion in 1966. They finally abandoned the rest of the branch in 1968. [1]

Penn Central Transportation

After the abandonment, there were heated rumors that the branch was now going to be sold to the Pennsylvania Railroad, the NYC's fierce competitor. However, the PRR ended up merging with the NYC that same year, forming the Penn Central Transportation Company. The Penn Central purchased the Catskill Mountain Branch that same year. The branch's eastern terminus was now at Bloomville and the route from Kingston to Rondout was in great disrepair with only three businesses keeping the line open.

Because of the poor condition, the Penn Central rarely ran trains on it. There were frequent derailments on the branch, and the train would have to go so slow, as to not derail, that it would sometimes take days for a single train to travel across the line. They replaced the ties to help with the derailment problems, but that only helped a little bit. The rails were also a problem as they were so old and deteriorated that they were at risk of collapse. After many problems with running the branch, the PC filed a petition with the ICC to abandon the branch finally abandoning it in 1976. [1]

Conrail

Template:Section-stub Also that year, a portion of the branch from Rondout to Kingston was purchased and operated by Conrail. The remainder was in extremely poor condition and was under state ownership. Conrail's portion was used to transport goods from the remaining customers of the branch to the junction at Kingston. From there, the goods would be transferred to the West Shore River Division for shipment to New York City and elsewhere. Conrail ran this small portion until 1979, when it decided it was no longer profitable. [1]

Kingston Terminal Railroad

Template:Section-stub In 1980, the Kingston Terminal Railroad (AAR reporting marks KTER) was organized to operate the approximately 5 miles of track between what is now the CSX River Division and Hudson Cement in East Kingston. Unfortunately, Hudson Cement closed in 1980 and the Kingston Terminal Railroad was dissolved having never operated a single train.

Present condition

Ulster County

Starting at Kingston Point, Milepost 0, the Trolley Museum of New York operates the trackage in Kingston east of the CSX River Line, up to about Milepost 2.5. The line in this section is owned by the City of Kingston and leased to the Trolley Museum. The Trolley Museum is focused on the preservation of the use of trolleys, and to restore the old Rondout Yard. They rebuilt the engine house in 1987, and the idea of rebuilding the utility building and the station has been suggested.

The next segment of the line, MP 2.8 in Kingston to MP 41.4 at the Delaware County line, is owned by Ulster County, which bought it from the Penn Central in 1979. The Catskill Mountain Railroad leases this portion of the line from Ulster County, and operates a tourist train from Phoenicia, MP 27.5 to just north of Cold Brook, MP 22.1. The tracks between Kingston and Cold Brook have been cleared for track car use, and are being upgraded for full train service from Kingston west towards Phoenicia. The Catskill Mountain Railroad is currently applying for funds to restore the line for tourist service to Ashokan, MP 16.2, as well as for freight service in Kingston. They are also working hard to restore a steam engine, former LS&I 23, owned by the Empire State Railway Museum, to eventually run the line from Kingston to Phoenicia.

The portion of the line between Phoenicia, MP 27.9, and Highmount, MP 41.4, also leased by the Catskill Mountain Railroad, is isolated by three large washouts west of Phoenicia, and has not seen a train since it was abandoned in 1976. However, a 2.5 mile section of the line, between Giggle Hollow (MP 38.9) and Highmount, home to the scenic "double horseshoe curve", was cleared for track car use was in 2006, by a joint team of members from the Trolley Museum, Catskill Mountain Railroad and Ulster & Delaware Railroad Historical Society.

In 2007, the clearing is planned to be extended to the Route 28 crossing in Shandaken (MP 33.6), despite two paved-over crossings and a weak bridge abutment in Big Indian (MP 36.4). The remaining six mile segment between Shandaken and the washouts just west of Phoenicia will be cleared in 2008.

The abandoned right-of-way from the Hunter and Kaaterskill branches in Ulster County can still be walked, despite all but one of the bridges being removed (there is only one surviving bridge on the branches, near the Ulster County-Greene County border line which is privately owned). There is also a washout along the old right-of-way in Chichester, that has exposed the soft, delicate clay underneath, and is very difficult to walk on.

Delaware County

The Delaware and Ulster Rail Ride, based in Arkville, MP 48.1, currently runs tourist trains from Highmount to Roxbury, MP 59.1. Currently the DURR's operations are limited to the portion between Arkville and Roxbury, as the line to Highmount is out of service due to a weak bridge abutment east of Arkville.

The pride of the DURR is the "Rip Van Winkle Flyer" a five-car Budd streamline train used for charters.

The regular train is powered by former D&H 5017, an Alco RS-36, and consists of two flat cars and three former PRR MP-53 coaches lettered for the New York Central.

Other engines at the DURR consist of Alco S-4s 1012 and 5106, and GE 44 tonner No. 76. Currently under restoration is the "Red Heifer" a Model 250 Brill Gas-Electric, formerly NYC M-405.

In Roxbury, the Roxbury Station is being restored by the Ulster & Delaware Railroad Historical Society and the Roxbury Station Museum is open, showcasing many artifacts and displays from the railroads mentioned above.

The Ulster & Delaware Railroad Historical Society owns: former NYO&W "Bobber" Caboose #8206, built at the NYO&W Middletown Shops in 1906; and former BEDT 14, a H. K. Porter Locomotive Works 0-6-0T steam locomotive, built in August 1920 at their facility in Pittsburgh, PA. Both are presently being restored by the Society.

The Delaware County ROW from Highmount to Bloomville is owned by the Catskill Revitalization Corporation.

The track ends at Hubbell Corners, MP 60.2, where the ROW becomes a rail trail that extends to Bloomville, MP 86.2, called the Catskill Scenic Trail.

As for the stations in Delaware County, the Halcottville Station, MP 53.0, was cut in half, with the passenger side moved a few hundred feet, where it serves as a shed on private property, and the freight side moved to Arkville, where it is now a tool shed for the Delaware and Ulster Rail Ride. The stations at South Kortright, MP 81.5, East Meredith, MP 97.9, and Davenport Center, MP 103.2, are currently private dwellings, with the railbed in front of them also being privately owned.

Interstate 88 was planned in the 1970s to go from Schenectady, New York to Binghamton, New York, although the original plans suggested that it go to New England and near the Atlantic Coast. The portion that was constructed covers a portion of the U&D's right-of-way in the township of Oneonta, where it connects with New York State Route 28.

Schoharie County

The South Gilboa Station, MP 70.6, is the only station on the remainder of the Ulster & Delaware that is in any state of poor condition. It is still in its original spot in between the Delaware County stations of Grand Gorge and Stamford. The old right-of-way in front of it is part of the Catskill Scenic Trail. It is also one of many buildings in the United States, including two other Ulster & Delaware railroad stations, that is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It has been proposed by the Town of Gilboa Historical Society that the South Gilboa station should have a full cosmetic restoration. However, this is only a proposal, and it is unclear whether it will take place.

Otsego County

The final station at Oneonta, MP 106.9, was part of a tourist line called the "Delaware and Otsego Railroad" that was created shortly after the portion was abandoned in the late 1960s. It ran trains from the station to a bridge that crossed Charlotte Creek a little ways from the old site of the West Davenport Station. However, it is currently a pub/restaurant called "The Depot". The line from Bloomville, MP 86.2 to Oneonta, MP 106.9, which was abandoned in 1965 with rails being removed shortly thereafter, is currently in the hands of private owners. [1]

Greene County

The Greene County portion of the branches, which were torn up in 1940, along with the smaller portion of the branches in Ulster County, remain as overgrown paths and bridge abutments, with an occasional road covering the ROW. New York State Route 214 overlaps where the former alignment at Stony Clove Notch. However, a two mile section of the line from Bloomer Road to Clum Hill Road in Tannersville has been converted into a rail trail known locally as the "Huckleberry Trail". There are also a few bridge piers; such as one on the southern side of the Esopus Creek in Phoenicia, one in Chichester (both in Ulster County), and two in Edgewood.

There are only two surviving stations on what used to be the branches. The Hunter Station, branch MP 2.5, is now a private dwelling. The Haines Falls Station, branch MP 18.5, is currently the headquarters of the Mountain Top Historical Society.

For more information about the disposition of the rest of the stations on the line, see the List of Ulster and Delaware Railroad Stations.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 John M. Ham, Robert K. Bucenec (2003), The Old "Up and Down" Catskill Mountain Branch of the New York Central, Stony Clove & Catskill Mountain Press

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Delaware, Ulster & Greene County NY Railroad Information (website), courtesy of Phillip M. Goldstein

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 John M. Ham, Robert K. Bucenec (2002), Light Rail and Short Ties Through the Notch: The Stony Clove & Catskill Mountain Railroad and Her Steam Legacy, Stony Clove & Catskill Mountain Press

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 John M. Ham, Robert K. Bucenec (2005), The Grand Old Stations and Steam Locomotives of the Ulster & Delaware, Stony Clove & Catskill Mountain Press