Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a British railway company and a notable example of civil engineering, linking London with the West Country, South West England and South Wales. It was founded in 1833, kept its identity through the 1923 grouping, and became the Western Region of British Railways at nationalisation in 1948.

Known admiringly to some as "God's Wonderful Railway", jocularly to others as the "Great Way Round" (some of its earliest routes were not the most direct), and by some as the "Goes When Ready" due to the casual way in which some of its branch lines were run, it gained great fame as the "Holiday Line", taking huge numbers of people to resorts in the southwest. The company's best-known livery was quite distinctive: locomotives were Middle Chrome Green (similar to Brunswick green), above Indian Red (later, plain black) frames; while the carriages were two-tone "chocolate and cream".

In 1999, in recognition of the railway's historical importance, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport added parts of the GWR to UNESCO's tentative World Heritage Sites list.[1] As of 2006, following the Brunel 200 celebrations, the nomination is being supported by English Heritage, and is due to be considered by UNESCO in 2007.[2]

Contents

Early history

The Great Western Railway originated from the desire of Bristol merchants to maintain the position of their port as the second port in the country and the chief one for American trade. The increase in the size of ships and the gradual silting of the [River Avon made Liverpool an increasingly attractive port, and with its rail connection with London developing in the 1830s it threatened Bristol's status. The answer for Bristol was, with the co-operation of London interests, to build a line of their own, a railway built to unprecedented standards of excellence to outperform the other lines being constructed to the north-west.

The Company was founded at a public meeting in Bristol in 1833, and was incorporated by Act of Parliament in 1835. Isambard Kingdom Brunel was appointed as engineer at the age of 27, and made two controversial decisions: to use a broad gauge of seven feet (actually 7 ft 0.25 in or 2140 mm) for the track, to allow large wheels, providing smoother running at high speeds; and to take a route which passed north of the Marlborough Downs, an area with no significant towns, though it did offer potential connections to Oxford and Gloucester and then to follow the Thames Valley into London. He surveyed the entire length of the route between London and Bristol himself.

G. T. Clark played an important role as an engineer on the project, reputedly taking the management of two divisions of the route including bridges over the River Thames at Basildon and Moulsford, and Paddington Station.[3] Involvement in major earth-moving works seems to have fed Clark's interest in geology and archaeology and he, anonymously, authored two guidebooks on the railway,[4][5], one illustrated with lithographs by John Cooke Bourne, in addition to a critique of Brunel's methods and the broad gauge.[6]

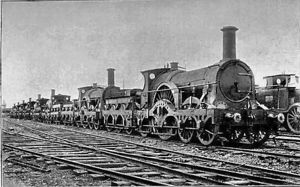

The initial group of locomotives ordered by Brunel to his own specifications proved unsatisfactory, apart from the North Star locomotive, and 20-year-old Daniel Gooch (later Sir) was appointed as Superintendent of locomotives. Brunel and Gooch chose to locate their locomotive works at the village of Swindon, at the point where the gradual ascent from London turned into the steeper descent to the Avon valley at Bath.

Openings

The first stretch of line, from London Paddington to Taplow near Maidenhead, opened in 1838. The full line to Bristol Temple Meads opened on completion of Box Tunnel in 1841.

From then onwards, by amalgamations and new construction, the railway took shape, as can be seen from the following list (dates are when opened/absorbed):

- Cheltenham and Great Western Union Railway: 1841 - 1845

- Oxford Railway 1843/1844

- Bristol and Exeter Railway 1844

- South Devon Railway 1844

- Berks and Hants Railway 1845/1846

- Oxford & Rugby Railway 1845/1846

- Birmingham & Oxford Junction Railway 1846/1848

- Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Dudley Railway 1846/1848

- Wilts, Somerset and Weymouth Railway 1848 - 1857

- South Wales Railway 1850 - 1856

- West Cornwall Railway 1852

- Shrewsbury & Birmingham Railway 1846-49/1854

- Shrewsbury & Chester Railway 1846/1854

- Wolverhampton Junction Railway 1852/1854

- Cornwall Railway 1859 - 1863

The Bristol and Exeter Railway reached Exeter by 1844, and the Bristol and Gloucester Railway brought the broad gauge to Gloucester in the same year. Gloucester was already served by the standard-gauge Birmingham and Gloucester Railway (opened throughout in 1841), resulting in a break of gauge, and the need for all passengers and goods travelling through Gloucester to change trains.

The GWR commissioned the world's first commercial telegraph line. This ran for 13 miles (21 km) from Paddington station to West Drayton and came into operation on 9 April 1839.

In 1846, the Great Western Railway took over the running of the Kennet and Avon Canal.

The "gauge war"

This was the beginning of the "gauge war", and resulted in the appointment by Parliament of a Gauge Commission, which duly moved in favour of standard gauge.

The undaunted GWR pressed ahead into the West Midlands, in hard-fought competition with the London and North Western Railway. Birmingham was reached in 1852, at Snow Hill (although the GWR had initially considered building to Rugby instead of Birmingham), Wolverhampton Low Level (the furthest-north broad-gauge station) and Birkenhead (on standard-gauge track) in 1854. The Bristol and Gloucester had been bought by the Midland Railway in 1846 and converted to standard gauge in 1854, bringing mixed gauge track (with three rails, so that both broad and standard gauge trains could run on it) to Bristol. By the 1860s the gauge war was lost; with the merger of the standard-gauge West Midlands Railway into the GWR in 1861 mixed gauge came to Paddington, and by 1869 there was no broad-gauge track north of Oxford.

Meanwhile, further developments were made in the GWR's heartland: the South Devon Railway (which for a time experimented with the “atmospheric” system of propulsion) was opened in 1849, extending the broad gauge to Plymouth, and the Cornwall Railway took it over the Royal Albert Bridge and into Cornwall, reaching Penzance by 1867. The South Wales Railway, terminating at Neyland, opened in 1850 and was connected to the GWR via Brunel's ungainly Wye bridge in 1852. The route from Wales to London via Gloucester was a roundabout one, so work on the Severn Tunnel began in 1873, but unexpected underwater springs slowed the work down and prevented its opening until 1886.

Through this period the conversion to standard gauge continued, with mixed-gauge track reaching Exeter in 1876. By this time most conversions were bypassing mixed gauge and going directly from broad to standard. The final stretch of broad gauge was converted to standard in a single weekend in May 1892.[7]

Into the Twentieth Century

Freed from what was by then the burden of the broad gauge, the 1890s also saw improvements in service of the generally conservative GWR - restaurant cars, much improved conditions for third class passengers, steam heating of trains, and accelerated express services. This was largely at the initiative of T. I. Allen, the Superintendent of the Line, and one of a group of talented senior managers who led the railway into the Edwardian era: Viscount Emlyn (Earl Cawdor), Chairman from 1895 to 1905; Sir Joseph Wilkinson, general manager from 1896-1903, and his successor, the former chief engineer Sir James Inglis; and George Jackson Churchward, William Dean's successor as Chief mechanical engineer from 1902 to 1922.[8]

Infrastructure

With its shares in demand from the later 1890s it was possible for the company to raise substantial sums from new issues to support the building of new lines and upgrading of old ones to shorten its previously circuitous routes.[9] The principal lines were

- South Wales & Bristol Direct Railway, from Wootton Bassett to the Severn Tunnel approaches on the outskirts of Bristol 1903

- Extension of Berks and Hants line completing a cut-off route to the West of England between Reading, Berkshire and Taunton 1906

- Birmingham Direct Line, from London to Aynho, chiefly joint with Great Central Railway 1906 - 1910

- Cheltenham and Honeybourne Railway 1906 and North Warwickshire line 1909, together giving a new route from Birmingham via Stratford-upon-Avon to Cheltenham and Bristol

- Swansea District Lines, avoiding Swansea in South Wales 1913

Related works included those at Fishguard Harbour in South Wales in an attempt to attract transatlantic liner traffic and the substantial rebuilding of Birmingham Snow Hill station.

New locomotives

After 1902 G. J. Churchward[10] developed nine standard locomotive types, with flat-topped Belpaire fireboxes, tapered boilers, long smokeboxes, boiler top feeds, long lap, long travel valve gear and many standard parts between locomotive types. Most of these were developed from five experimental locomotives, No's 40, 97, 98, 99 and 115. From these were developed the famous Star class locomotives, the Saint class locomotives and the 2800 class locomotives. Such was the success of these locomotives that they influenced locomotive design in the United Kingdom until the demise of steam traction. Two notable locomotives were 111 The Great Bear, the first 4-6-2 locomotive in the United Kingdom and 3440 City of Truro, the first locomotive to be recorded at a speed of 100 mph (160 km/h) in 1904 (although this speed has never been formally confirmed).

Churchward also remodelled Swindon works, building the one-and-a-half-acre (6,000 m²) boiler-erecting shops and the first static locomotive-testing plant in the United Kingdom.

1923 Grouping

At the outbreak of World War I the GWR, along with the other major railways, was taken into government control. After the war the government considered permanent nationalisation, but preferred a compulsory amalgamation of the railways into four large groups. The GWR alone preserved its identity through the grouping, which took effect on 1 January 1923.

Constituent companies

The new Great Western Railway comprised the following constituent companies:

- Great Western Railway, route length 3005 miles (4836 km)

- Barry Railway 68 miles (109 km)

- Cambrian Railways 295.25 miles (475.1 km)

- Cardiff Railway 11.75 miles (18.9 km)

- Rhymney Railway 51 miles (82 km)

- Taff Vale Railway 124.5 miles (200.4 km)

- Alexandra (Newport and South Wales) Docks and Railway 10.5 miles (16.9 km)

Total route length of the GWR was 3800 miles (6116 km)

One final company was absorbed, in 1930 - the narrow gauge Corris Railway.

Other statistics

- Locomotives: tender 1550, tank 2500; coaching vehicles 10,100; freight vehicles 90,000; electric vehicles 60; rail motor cars 70

- 213 miles (343 km) of canals

- 16 turbine and twin-screw steamers, plus several smaller vessels

- docks, harbours etc at Barry, Cardiff, Fishguard, Newport, Penarth, Plymouth, Port Talbot and other places

- ten hotels

Much of the inherited infrastructure had come into being for handling the South Wales coal traffic. Though this appeared to be a great coup for the GWR, the coal traffic declined significantly as the use of coal as a naval fuel declined, and within a decade the GWR was itself the largest single user of Welsh coal.

New locomotives (1920s)

The 1920s also saw the introduction of the GWR's most famous locomotives - the Castle and King classes developed by Churchward's successor, C. B. Collett. The 1930s brought hard times, and the records set by the Castles and Kings were surpassed by other companies, but the company remained in relatively good financial health despite the Depression.

Post WWII

Nationalisation

World War II brought a further period of direct government control, and by its end a Labour government was in power and planning to nationalise the railways. The war-damaged GWR became part of British Railways on 1 January 1948. One of the last Directors of the GWR, Harold Macmillan, was instrumental in the defeat of the Labour Government by the Conservatives, led then by Winston Churchill, in the [1951 General Election and later himself became Prime Minister in 1957.

Preservation

The traditions of the GWR are kept alive by many heritage railways including at Didcot Railway Centre, the South Devon Railway, the Severn Valley Railway, the Paignton and Dartmouth Steam Railway, the Gloucestershire and Warwickshire Railway, the Dean Forest Railway, Telford Steam Railway, West Somerset Railway and at Tyseley Locomotive Works. The STEAM museum, Swindon, The Gwili Steam Railway Carmarthen (West Wales) is dedicated to the history and life of the GWR.

- Further information: List of British heritage and private railways

Revival of name

On privatisation of the railways in the early 1990s, the "Great Western" name was revived for the train operating company providing passenger services to the West. Services are now run under the franchise name First Great Western.

Cultural references

The Great Western Railway was immortalised in Bob Godfrey's Oscar winning 1975 animated film "Great", which tells the story of Brunel's engineering accomplishments. The film features poignant shots of disused and neglected GWR engines to the background of a specially written song entitled 'GWR':

GWR, we've never been that far, Brunel has had his first success. When he drew up the plans, the company said yes, that's how they opened up the west, it's too spectacular, it's GWR!

The film won the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film of 1975.

The Great Western Railway was also the subject of a BBC children's television series God's Wonderful Railway, which aired in 1980.

In the 1970 film The Railway Children the Old Gentleman's train is hauled by Great Western Railway pannier tank No. 5775.

In the children's television series Thomas the Tank Engine and Friends, two characters come from the Great Western Railway: Duck and Oliver. Both characters also come from The Railway Series books.

Manic Street Preachers lead vocalist James Dean Bradfield's first solo album was named The Great Western, most likely being a reference to the trips he took to London from his home in South Wales.

See also

Notes

- ↑ UNESCO (2007)

- ↑ Morris (2006)

- ↑ James, B. Ll. (2004) "Clark, George Thomas (1809–1898)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, accessed 21 August 2007 Template:ODNBsub

- ↑ [Clark, G. T.] (1839) Guidebook to the Great Western Railway

- ↑ [Clark, G. T.] (1846) The History and Description of the Great Western Railway

- ↑ (1895) Gentleman's Magazine, 279, 489–506

- ↑ Clinker, C. R. (1978). New light on the Gauge Conversion. Bristol: Avon-AngliA. ISBN 0-905466-12-8.

- ↑ MacDermot, vol. 2

- ↑ Norris, John; Gerry Beale, John Lewis (1987). Edwardian Enterprise: a review of Great Western Railway development in the first decade of this century. Didcot: Wild Swan Publications. ISBN 0-906867-39-8.

- ↑ Rogers, H. C. B. (1975). G. J. Churchward - A Locomotive Biography. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-385069-3.

References

- Bryan, T. (2004) All in a Day's Work: Life on the GWR, Ian Allan, ISBN 0-7110-2964-4

- Great Western Railway (1904) Rules and Regulations - For the Guidance of the Officers and Men, Reprinted 1993, Ian Allan, ISBN 0-7110-2259-3

- MacDermot, E.T. (1964) History of the Great Western Railway. Volume One: 1833-1863, Reprinted 1982, Ian Allan, ISBN 0-7110-0411-0

- MacDermot, E.T. (1964) History of the Great Western Railway. Volume Two: 1863-1921, Reprinted 1982, Ian Allan, ISBN 0-7110-0412-9

- Morris, S. (2006) God's Wonderful Railway on track to be world heritage site, Guardian Unlimited 7 July 2006, www site [accessed 19 May 2007]

- Nock, O.S. (1962) The Great Western Railway in the nineteenth century, Ian Allan

- Nock, O.S. (1964) The Great Western Railway in the twentieth century, Ian Allan

- Nock, O.S. (1967) History of the Great Western Railway. Volume Three: 1923-1947, Reprinted 1982, Ian Allan, ISBN 0-7110-0304-1

- Tourret, R. (2003) GWR Engineering Work, 1928-1938, Tourret Publishing, ISBN 0-905878-08-6

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2007) The Great Western Railway: Paddington-Bristol (selected parts), Tentative Lists Database, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, www site [accessed 19 May 2007]

- Vaughan, Adrian (1990), Signalman's Reflections, Silver Link Publishing, ISBN 0-947971-54-8

External links

- Description of the work required for the conversion from broad to narrow gauge

- GWR Modelling

- Great Western heritage rolling stock

- The West Somerset Steam Railway Trust, An organisation preserving the history of the GWR and the Minehead Branch

The "Big Four" pre-nationalisation British railway companies

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

█ Great Western • █ London Midland & Scottish • █ London & North Eastern • █ Southern | ||

|

GWR constituents:

Great Western Railway •

Cambrian Railways •

Taff Vale Railway | ||

|

See also: History of rail transport in Great Britain 1923 - 1947 • List of companies involved in the grouping | ||