Trans-Siberian Railway

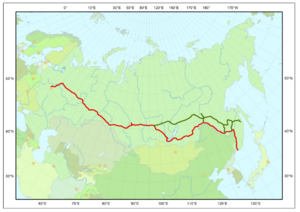

The Trans-Siberian Railway or Trans-Siberian Railroad (Транссибирская магистраль, Транссиб in Russian, or Transsibirskaya magistral', Transsib) is a network of railways connecting Moscow and European Russia with the Russian Far East provinces, Mongolia, China and the Sea of Japan.

Contents

History

The main route, the Trans-Siberian, runs from Moscow to Vladivostok via southern Siberia and was built between 1891 and 1916. It is often associated with the main Russian train that connects these two cities. At 9,288 kilometres (5,772 miles), spanning 8 time zones and taking about 7 days to complete its journey, it is the third longest single continuous service in the world, after the Donetsk-Vladivostok and Moscow-Pyongyang services, both of which follow the Trans-Siberian.

A second primary route is the Trans-Manchurian, which coincides with the Trans-Siberian as far as Tarskaya (a stop 12 km east of Karymskaya, in Chita Oblast), about 1000 km east of Lake Baikal. From Tarskaya the Trans-Manchurian heads southeast, via Harbin and Mudanjiang in China's Northeastern Provinces (from where a connection to Beijing is used by one of Moscow-Beijing trains), joining with the main route in Ussuriysk just north of Vladivostok. This is the shortest and the oldest rail route to Vladivostok.

The third primary route is the Trans-Mongolian, which coincides with the Trans-Siberian as far as Ulan Ude on Lake Baikal's eastern shore. From Ulan-Ude the Trans-Mongolian heads south to Ulaan-Baatar before making its way southeast to Beijing.

In 1991, a fourth route running further to the north was finally completed, after more than five decades of sporadic work. Known as the Baikal Amur Mainline (BAM), this recent extension departs from the Trans-Siberian line at Taishet several hundred miles west of Lake Baikal and passes the lake at its northernmost extremity. It crosses the Amur River at Komsomolsk-na-Amure (north of Khabarovsk), and reaches the Pacific at Sovetskaya Gavan (i.e., "Soviet Haven", a.k.a. Sovgavan, Sovietgavan, and earlier Imperatorskaya Gavan, i.e., "Imperial Haven"). While this route provides access to Baikal's stunning northern coast, it also passes through some rather forbidding terrain.

Demand and design

In the late 19th century, the development of the Siberia was hampered by poor transportation links within the region as well as between Siberia and the rest of the country. Good roads suitable for wheeled transport were few and far apart. For about 5 months of the year, rivers were the main means of transportation; during the cold half of the year, cargo and passengers traveled by horse-drawn sleds over the winter roads, many of which were the same rivers, now ice-covered.

The first steamboat on the Ob, Nikita Myasnikov's "Osnova", was launched in 1844; but the early starts were difficult, and it was not until 1857 that steamboat shipping started developing in the Ob system in the serious way. Steamboats started operating on the Yenisei in 1863, on the Lena and Amur in the 1870s.

While the comparably flat Western Siberia was at least fairly well served by the gigantic Ob-Irtysh-Tobol-Chulym river system, the mighty rivers of Eastern Siberia -- Yenisei, Upper Angara River (Angara River below Bratsk was not easily navigable because of the rapids), Lena -- were mostly navigable only in the north-south direction. An attempt to somewhat remedy the situation by building the Ob-Yenisei Canal were not particularly successful. Only a railroad could be a real solution to the region's transportation problems.

The first railroad projects in Siberia emerged after the creation of the Moscow-Saint Petersburg Railway.[1] One of the first was the Irkutsk-Chita project, intended to connect the former to the Amur river, and consequently, to the Pacific Ocean. On the initiative of Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky, surveys for a railroad in the Khabarovsk region were conducted.

Before 1880, the central government had virtually ignored these projects, because of the weakness of Siberian enterprises, a clumsy bureaucracy, and fear of financial risk. Financial minister Count Egor Kankrin wrote:

The idea of covering Russia with a railroad network not just exceeds any possibility, but even building the railway from Petersburg to Kazan must be found untimely by several centuries.[2]

The abovementioned Irkutsk-Chita project, proposed by an American entrepreneur W. Collins, was rejected by the government, and a lesson was given to the major-general Muravyov-Amurskiy who "thoughtlessly showed benevolence" to the American project. Thus, the government tried to prevent the American and British sphere of influence in the Pacific from extending to Siberia.

By 1880, there were a large number of rejected and upcoming applications for permission to construct railways to connect Siberia with the Pacific but not eastern Russia. This worried the government and made connecting Siberia with central Russia a pressing concern.

The design process lasted 10 years. Along with the route actually constructed, alternative projects were proposed:

- Southern route: via Kazakhstan, Barnaul, Abakan and Mongolia

- Northern route: via Tyumen, Tobolsk, Tomsk, Yeniseysk and the modern Baikal Amur Mainline or even through Yakutsk.

According to a legend, the line originally had an unneeded 7km loop, which was due to the fact that during planning, the Russian Tsar accidentally had part of his finger in the way of plotting the route, and construction workers were too afraid of mentioning the mistake to the Tsar, resulting in them building the line including this "error". (Lonely Planet, Trans-Siberian Railway, first edition. This legend is more often told about the much earlier Moscow-Saint Petersburg Railway.)

Railwaymen fought against suggestions to save funds, for example, by installing ferryboats instead of bridges over the rivers until traffic increased. The designers insisted and secured the decision to construct an uninterrupted railway.

Unlike the rejected private projects, that intended to connect the existing cities demanding transport, the Trans-Siberian did not have such a priority. Thus, to save money and avoid collisions with land owners, it was decided to lay the road aside the existing cities. Tomsk was the largest city, and the most unfortunate, because the swampy banks of the Ob river near it was considered inappropriate for a bridge. The railway was laid 70 km to the south, just a blind branch line connected with Tomsk, depriving the city of the prospective transit rail traffic and trade.

The railway was instantly filled to its capacity with local traffic, mostly wheat. Together with low speed and low possible weights of trains, it upset the promised role as a transit route between Europe and East Asia. During the Russian-Japanese war, the military traffic to the East almost disorganized the civic freight flow.

Construction

Full time construction on the Trans-Siberian Railway began in 1891 and was put into execution and overseen by Sergei Witte, who was then Finance Minister.

Similar to the First Transcontinental Railroad in the USA, Russian engineers started construction at both ends and worked towards the center. From Vladivostok the railway was laid north along the right bank of the Ussuri River to Khabarovsk at the Amur River becoming the Ussuri railway.

In 1890, a bridge across the river Ural was built and the new railroad entered Asia. The bridge across the Ob River was built in 1898 and the small city Novonikolaevsk, founded in 1883, metamorphosed into a large Siberian center—Novosibirsk city. In 1898, the first train reached Irkutsk and the shore of Lake Baikal. The railroad ran on to the East, across the Shilka and the Amur rivers and soon reached Khabarovsk. The Vladivostok-Khabarovsk branch was built a bit earlier, in 1897.

Convict labour, from Sakhalin Island and other places, and Russian soldiers were drafted into railway-building service. One of the largest obstacles was Lake Baikal, some 60 km (40 mi) east of Irkutsk. Lake Baikal is more than 640 km (400 mi) long and over 1,600 m (5,000 feet) deep. The line ended on each side of the lake and a special icebreaker ferryboat was purchased from England to connect the railway. In the winter sleighs were used to move passengers and cargo from one side of the lake to the other until the completion of the Lake Baikal spur along the southern edge of the lake. With the completion of the Amur River line north of the Chinese border in 1916, there was a continuous railway from Petrograd to Vladivostok that remains to this day the world's longest railway line.

Electrification of the line, begun in 1929 and completed in 2002, allowed a doubling of train weights to 6,000 tonnes.

Effects

The Trans-Siberian Railway gave a great boost to Siberian agriculture, facilitating substantial exports to central Russia and Europe. It influenced the territories it connected directly, as well as those connected to it by river transport. For instance, Altai Krai exported wheat to the railway via the Ob river.

As Siberian agriculture began to export cheap grain towards the West, agriculture in Central Russia was still under economic pressure after the end of serfdom, which was formally cancelled in 1861. Thus, to defend the central territory and to prevent possible social destabilization, in 1896, the government introduced the Chelyabinsk tariff break (Челябинский тарифный перелом), a tariff barrier for grain passing through Chelyabinsk, and a similar barrier in Manchuria. This measure changed the nature of export: mills emerged to create bread from grain in Altai, Novosibirsk and Tomsk, and many farms switched to butter production. From 1896 until 1913 Siberia exported averagely 501,932 tonnes (30,643,000 pood) of bread (grain, flour) annually.[3]

The Trans-Siberian line remains the most important transportation link within Russia; around 30% of Russian exports travel on the line. While it attracts many foreign tourists, it also gets considerable use from domestic passengers.

Today the Trans-Siberian Railway carries about 20,000 containers per year to Europe, including 8,300 containers from Japan. This is a fairly small amount, considering that for all means of transport combined Japan sends 360,000 containers to Europe per year. Thus, there is potential for growth, and the Russian Ministry of Transport planned to increase the number of containers shipped on the railway to 100,000 by the year 2005 and satisfy the passage and cargo needs of 120 trains per day. This required that stretches that were single track and formed a bottleneck would be made double track.

Costs

The train has 2nd class 4-berth compartments (called kupé) and 1st class 2-berth compartments (called spalny wagon or 'SV') and a restaurant car. One-way fares start at about $200 in a 4-berth sleeper or $320 in a 2-berth sleeper. [4] Prices increase dramatically if additional stops are needed. Russian train tickets can only be purchased within the Russian Federation or in Finland. Tickets can be purchased only 45 days in advance. Many travel agencies can arrange to have tickets purchased by proxy, but the 45 day limit is strictly enforced.

Routes

Trans-Siberian line

A commonly used main line route is as follows. Distances and travel times are from the schedule of train No.002M, Moscow-Vladivostok.[5]

- Moscow, Yaroslavsky Rail Terminal (0 km, Moscow Time).

- Vladimir (210, km, MT)

- Nizhny Novgorod (461 km, 6 hours, MT) on the Volga River. Its railroad station is still called by its old Soviet name Gorky, and is so listed in most timetables

- Kirov (917 km)

- Perm (1397 km, 20 hours, MT+2) on the Kama River

- Official boundary between Europe and Asia (1777 km), marked by a white obelisk

- Yekaterinburg (1778 km, 1 day 2 h, MT+2) in the Urals, still called by its old Soviet name Sverdlovsk in most timetables

- Tyumen (2104 km)

- Omsk (2676 km, 1 day 14 h, MT+3) on the Irtysh River

- Novosibirsk (3303 km, 1 day 22 h, MT+3) on the Ob River

- Krasnoyarsk (4065 km, 2 days 11 h, MT+4) on the Yenisei River

- Taishet (4483 km), junction with the Baikal-Amur Mainline

- Irkutsk (5153 km, 3 days 4 h, MT+5) near Lake Baikal's southern extremity

- Ulan Ude (5609 km, 3 days 12 h, MT+5)

- Junction with the Trans-Mongolian line (5622 km)

- Chita (6166 km, 3 days 22 h, MT+6)

- Junction with the Trans-Manchurian line at Tarskaya (6274 km)

- Birobidzhan (8312 km, 5 days 13h), the capital of Jewish Autonomous Region

- Khabarovsk (8493 km, 5 days 15 h, MT+7) on the Amur River

- Ussuriysk (9147 km), junction with the Trans-Manchurian line

- Vladivostok (9259 km, 6 days 4 h, MT+7), on the Pacific Ocean

There are many alternative routings between Moscow and Siberia. For example:

- Some trains would leave Moscow from Kazansky Rail Terminal instead of Yaroslavsky Rail Terminal; this would shave some 20 km off the distances, because it provides a shorter exit from Moscow onto the Nizhny Novgorod main line.

- One can take a night train from Moscow's Kursky Rail Terminal to Nizhny Novgorod, make a stopover in the Nizhny and then transfer to a Siberia-bound train

- From 1956 to 2001 many trains went between Moscow and Kirov via Yaroslavl instead of Nizhny Novgorod. This would add some 29 km to the distances from Moscow, making Vladivostok Kilometer 9288.

- Other trains get from Moscow (Kazansky Terminal) to Yekaterinburg via Kazan.

- Between Yekaterinburg and Omsk it is possible to travel via Kurgan Petropavl (in Kazakhstan) instead of Tyumen.

- One can bypass Yekaterinburg altogether by travelling via Samara, Ufa, Chelyabinsk, and Petropavl; this was historically the earliest configuration.

Depending on the route taken, the distances from Moscow to the same station in Siberia may differ by several tens of kilometers.

Trans-Manchurian line

The Trans-Manchurian line, as e.g. used by train No.020, Moscow-Beijing[6] follows the same route as the Trans-Siberian between Moscow and Chita, and then follows this route to China:

- Branch off from the Trans-Siberian-line at Tarskaya (6274 km from Moscow)

- Zabaikalsk (6626 km), Russian border town

- Manzhouli (6638 km from Moscow, 2323 km from Beijing), Chinese border town

- Harbin (7573 km, 1388 km)

- Changchun (7820 km from Moscow)

- Beijing (8961 km from Moscow)

The express train (No.020) travel time from Moscow to Beijing is just over 6 days.

There is no direct passenger service along the entire original Trans-Manchurian route (i.e., from Moscow -- or anywhere in Russia-west-of-Manchuria -- to Vladivostok via Harbin), due to the obvious administrative and technical (gauge break) inconveniences of crossing the border twice. However, assuming sufficient patience and possession of appropriate visas, it is still possible to travel all the way along the original route, with a few stopovers (e.g. in Harbin, Grodekovo, and Ussuriysk). [7] [8] [9] That would pass the following points from Harbin east:

- Harbin (7573 km from Moscow)

- Mudanjiang (7928 km)

- Suifenhe (8121 km), the Chinese border station

- Grodekovo (8147 km), Russia

- Ussuriysk (8244 km)

- Vladivostok (8356 km)

Trans-Mongolian line

The Trans-Mongolian line follows the same route as the Trans-Siberian between Moscow and Ulan Ude, and then follows this route to Mongolia and China:

- Branch off from the Trans-Siberian line (5655 km from Moscow)

- Naushki (5895 km, MT+5), Russian border town

- Russia-Mongolia border (5900 km, MT+5)

- Sühbaatar (5921 km, MT+5), Mongolian border town

- Ulaan-Baatar (6304 km, MT+5), the Mongolian capital

- Trans Mongolian train ticket booking: from Mongolian capital Ulaanbaatar to Irkutsk, Novosibirsk, Ekaterinburg, Moscow or to Datung, Beijing. www.traveltomongolia.mn

- Zamiin Uud (7013 km, MT+5), Mongolian border town

- Erlian (842 km from Beijing, MT+5), Chinese border town (二连浩特)

- Datong (371 km, MT+5)

- Beijing (MT+5)

Trivia

- Since Russia and Mongolia use broad gauge railways while China uses the standard gauge, there is a break-of-gauge, meaning that carriages to or from China cannot simply cross the border, and each carriage has to be lifted in turn to have its bogies changed. The whole operation, combined with passport and customs control, can take several hours.

- The lower the train number the fewer stops it makes and therefore the faster the journey. Unfortunately, the train number makes no difference to the duration of border crossings.

- The Trans-Siberian Railway is the theme for the 1900 Trans-Siberian Railway Fabergé egg.

- The Trans-Siberian Railway is longer than both the Great Wall of China and US Route 66.

See also

References

- Thomas, Bryn (2003). The Trans-Siberian Handbook (6th Ed). Trailblazer. ISBN 1-873756-70-4

- ↑ Based on a chapter of: Problem Regions of Resourse Type: Economical Integration of European North-East, Ural and Siberia. / Managing editors: V. V. Alexeev, M. K. Bandman, V. V. Kuleshov — Novosibirsk, IEIE, 2002. ISBN 5-89665-060-4

- ↑ Столетие железных дорог // Труды научно-технического комитета Комиссариата путей сообщения. Вып.20 — М., 1925. Century of Railways // Works of scientific and technical committee of Communications Comissariat. Issue 20 — Moscow, 1925.

- ↑ Храмков А. А. Железнодорожные перевозки хлеба из Сибири в западном направлении в конце XIX — начале XX вв. // Предприниматели и предпринимательство в Сибири. Вып.3: Сборник научных статей. Барнаул: Изд-во АГУ, 2001.

Khramkov A. A. Railroad Transportation of Bread from Siberia to the West in the Late XIX — Early XX Centuries. // Entrepreneurs and Business Undertakings in Siberia. 3rd issue. Collection of scientific articles. Barnaul: Altai State University publishing house, 2001. ISBN 5-7904-0195-3 - ↑ Ticket prices change often. Taken from:How to Travel by Trans-Siberian Railway from London to China & Japan Accessed October 20, 2006

- ↑ [http://www.poezda.net/en/train_timetable?st_code=2000002&forDate=11-11-2006&tr_code=545554%3A%C0+ Timetable for train No.2, Moscow-Vladivostok] (Accessed 20006-Nov-3)

- ↑ Timetable for train No. 020, Moscow-Beijing, November 2006

- ↑ Harbin-Suifenhe train schedule

- ↑ Grodekovo-Harbin schedule, Nov 2006 (Note that Russian train sites give incorrect kilometer distance between Chinese stations)

- ↑ Grodekovo-Ussuriysk schedule, Nov 2006

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Trans-Siberian railway |

- {{{2}}} travel guide from Wikitravel

- The Trans-Siberian Railway: Web Encyclopedia

- Transportation Overview in the Khabarovsk Krai Region of Russia from U.S. Department of State

- Map

- The site about railways in C.I.S. and Baltics

- Guide to the Great Siberian Railway (1900)

- Google Earth Trans-Siberian Railway placemarks and path

- From London to Japan by train and ferry

- Siberia (Сибирь) in Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (Russian)

- Siberian railroad (Сибирская железная дорога) in Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (Russian)

- The Great Siberian Railway, in The North American Review (Volume 170, Issue 522, May 1900).

- The New Student's Reference Work/Siberian Railroad (1914)

Travel tales:

- From Ulaanbaator to Moscow

- The Australian Broadcasting Corporation's Moscow correspondent writes a travel blog about her trip on the Trans-Siberian.

Commercial Links

The following are links to commercial sites, such as online stores, and may or may not provide useful additional information for this article. No endorsement of any commercial link is implied by its presence here:

- For timetables, see Travel planner of German Railways (covers Europe, as well as at least each branch of the Trans-Siberian Railway) and time-table with distances (pdf); note that Moscow time applies for railways throughout Russia.

- Travel Planner for Trans-Siberian, Trans-Manchurian and Trans-Mongolian Railways with real time train schedules

- Travel To Mongolia – The Trans-Mongolian Railway

- WayToRussia – Guide to the Trans-Siberian Railway.